The Agricultural Revolution and Its Consequences

And Why We've Been Miserable Ever Since

Hi, I’m an existential imbecile named Max Murphy. Here on The Murphy Memos we explore the absurdity of existence.

Consider subscribing if you’re into that kinda thing.

You’ve probably never heard of Helena Valero, but her story holds a key to one of history’s greatest contradictions.

She was a Brazilian woman captured by the Yanomami tribe. Initially a prisoner, she was eventually freed, built a life, raised a family, and spent over twenty years with them.

When she finally returned to civilization, she did something that shocked everyone: she chose to go back to the Yanomami for good.

Whenever someone has an adequate understanding of both worlds, they almost always choose the “uncivilized” one.

And today, my friend, we’re going to find out why.

Take it or Leave it

For centuries, our view of civilization has been dominated by two iconic thinkers who represent diametrically opposed perspectives:

Thomas Hobbes: saw the natural world as a “war of all against all” and life under an oppressive Leviathan state is preferable.

Jean Jacques Rousseau: argued the opposite. “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains” contending that civilization itself is a source of misery.

Today, we finally have enough evidence to declare a winner: by and large, Rousseau was right. The spiritual malaise, the profound dissatisfaction, the inescapable feeling of captivity despite all our “freedom.”

Civilization breeds discontent.

Helena Valero represents a consistent pattern throughout centuries of history. America’s greatest polymath, Benjamin Franklin, even noticed it too:

“When an Indian Child has been brought up among us, taught our language and habituated to our Customs, yet if he goes to see his relations and make one Indian Ramble with them there is no persuading him ever to return… when white persons of either sex have been taken prisoner young by the Indians, and lived awhile among them, tho’ ransomed by their Friends, and treated with all imaginable tenderness to prevail with them to stay among the English, yet in a Short time they become disgusted with our manner of life, and the care and pains that are necessary to support it, and take the first opportunity of escaping again into the Woods, from whence there is no reclaiming them.”

According to Franklin, even wealthy people heard the wilderness calling:

“One instance I remember to have heard, where the person was to be brought home to possess a good Estate; but finding some care necessary to keep it together, he relinquished it to a younger brother, reserving to himself nothing but a gun and match-Coat, with which he took his way again to the Wilderness.”

Now, this conversation easily devolves into noble savage romanticism–the idea that “primitive” people are these angelic archetypes representing all that is good about the human condition. But this narrative is simplistic and wrong as Graeber reminds us, “Helena Valero was herself adamant on this point. The Yanomami were not devils, she insisted, neither were they angels. They were human, like the rest of us.”

The real divide, then, isn’t between the civilized vs savage, but between two opposing stories about humanity’s place in the world.

In his award-winning novel, Ishmael, Daniel Quinn coined two terms that’ll be helpful here:

Takers: heirs to the agricultural revolution who live as if the world is something for them to conquer, dominate, and possess. Always in pursuit of “more.”

Leavers: pastoral, tribal, and hunter-gatherer societies (like the Yanomami) who see themselves as members of the community of life rather than its masters.

Quinn explained that there are certain laws of nature that cannot be broken. Imagine a man who believes he can fly because he invented wings. He jumps off a cliff. Begins flapping, and for a brief moment, it appears that he can, in fact, fly.

But he begins descending, slowly at first.

“No worries” he thinks to himself, “I just need to flap my wings a bit harder.”

But the laws of aerodynamics catch up with him eventually. He plummets to a terrible death.

Our entire civilization is that man.

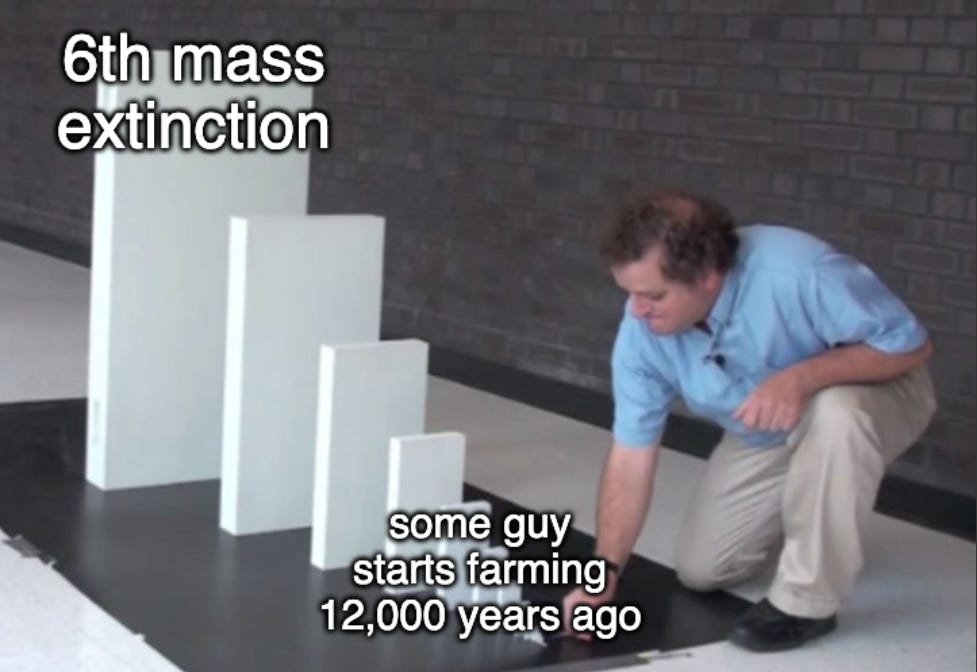

We’ve been flapping our wings for 12,000 years, convinced that more effort, more technology, and more control will finally make our flight sustainable.

But the law is the law. Our descent is now undeniable.

But it raises a serious question: why did we jump off a cliff in the first place?

Rotten Apples

The most common interpretation of the story of Adam and Eve is that the devil—assuming the form of a snake—tempted Eve, who ate the forbidden fruit: an apple that represented the knowledge of good and evil.

If we’re being honest here, has that interpretation ever made sense to you? Me either.

What if we’ve been reading it wrong for millennia? What if the story isn’t about morality at all, but is a much older, more profound warning encoded as myth?

This is where Quinn’s reading becomes essential. The “Forbidden Fruit” isn’t the knowledge of good and evil—it’s the knowledge of agriculture.

If only we’d listened to Charlie XCX: “I think the apple’s rotten right to the core”

Think about it. What is the first consequence of eating the apple? They’re cast out of the hunter-gatherer paradise of Eden and into a world of toil. “By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food,” God says.

Does that sound like a punishment for gaining abstract knowledge? Or does it sound like a condemnation to the back-breaking job of farming?

The Apple represents the moment we discovered we could plant seeds and cultivate the land. This was the birth of the surplus—the ability to grow and stockpile more food than we needed. And with that single innovation, everything changed.

A permanent food surplus enabled the world we know and hate: it allowed for permanent settlements, which grew into towns and cities—and offices filled with human bodies driven only by caffeine and antidepressants.

It enabled specialization, creating priests, kings, and soldiers—a hierarchy to manage and protect the surplus. This was the genesis of civilization itself.

The chains Rousseau identified were not made of iron, but of wheat and barley.

This is the true “Original Sin”: breaking the fundamental law of life that we belong to the world, not the other way around.

Those Neolithic farmers didn’t know it at the time, but they were forcing humanity off that cliff.

The entire, tumultuous history of civilization—with all its empires and anguish—is just us, falling through the air, flapping our wings and telling ourselves we’re flying.

But the story doesn’t end there. The very next chapter in Genesis shows us the ultimate consequence of this new way of life.

Genesis of Genocide

The story of Cain and Abel is often treated as a simple morality tale about jealousy. But through Quinn’s lens, it reads as the original manifesto of Taker culture, a pattern of behavior that has defined the last 12,000 years.

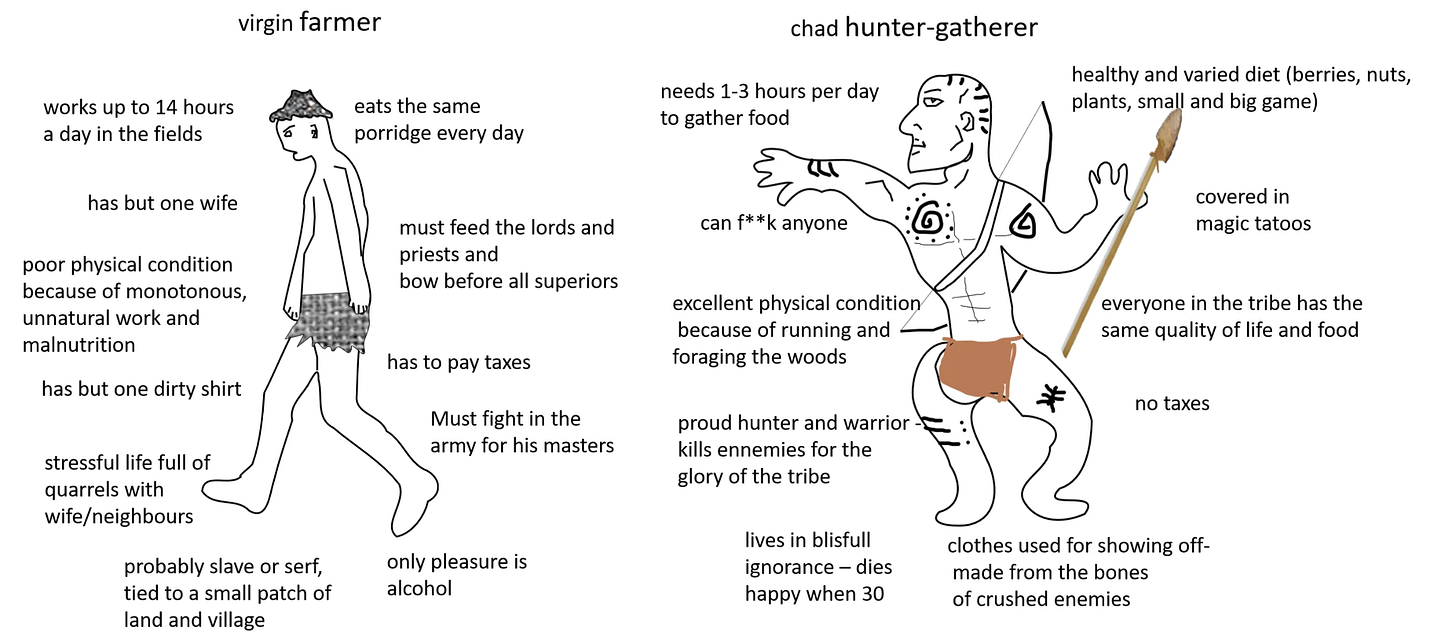

Abel, the nomadic herdsman, is the original Chad. He lives in harmony with nature, his needs are met, and most importantly, his “work” wasn’t the soul-crushing toil we know today.

As Peter Gray explains, the data suggests that for hunter-gatherers, productive activities were often social, skilled, and voluntary—blurring the line between work and play.

Leavers are the original affluent society not because they had so much, but because their wants were few and their labors were human.

Abel offers a sacrifice from his flock that requires only participation in the natural cycle. God looks upon it with favor.

Then there’s Cain, the settled farmer—the archetypal Soyjack: sweating, insecure, and seething with resentment. His life is defined by the back-breaking labor prophesied in Eden.

Cain offers the fruits of his struggle, his attempt to control and dominate mother earth.

God rejects it.

In an envious rage, Cain murders his brother. This is the Taker’s ultimate response to the Leaver: if your way of life is a living critique of mine, I will annihilate you.

When God asks, “Where is your brother Abel?” Cain delivers the line that has echoed throughout millennia of conquest and genocide: “Am I my brother’s keeper?”

So, not only did this story predict the relentless genocide against Leaver peoples, but it also highlights the Taker’s refusal to take responsibility for the destruction left in their wake.

From Caesar’s massacre of Gaul to the brutality of European colonialism, a clear pattern emerges: history is drowning in the blood of Leaver peoples.

And when God asks the conquerors what they have done to their fellow man, the Takers shrug their shoulders.

Cain’s response isn’t just a lie but a philosophical stance: I am not responsible for what I destroy. A mistake that will come back to haunt him.

But this forces a deeper question: how can Cain—a murderer who lies to God—be religious? Does Cain worship God? Do you even pray, bro?

The shocking answer is yes, Cain is deeply religious. He just worships something other than God.

The God of “More”

Cain’s god was not the God of Abel. Cain’s god was the god of the surplus, the god of More, the god of the controlled and the dominated. This is the deity the Book of Matthew warns us about: “You cannot serve both God and Mammon.”

Mammon—an Aramaic word for money—became in Medieval Europe a demonic personification of worldly success. But it’s more accurate to see Mammon as another god, offering a theology in direct opposition to Christ. Where Jesus preaches renunciation, Mammon preaches acquisition.

His command—The Mammonian More—is the core theology of Taker culture.

The agricultural surplus, no matter how large, is never enough for Mammon. He demands More. As food becomes more abundant, the population increases, spawning a vicious cycle of more demanding more demanding more, until the entire world is swallowed by a species living in its own bondage.

Just as a cancer cell demands infinite growth until the host dies, so too does Mammon demand More until the whole planet dies.

Mammon is a mind virus, a death cult that has hijacked our species, convincing us that the only noble pursuit is relentless, metastatic expansion. This is the engine of the Sixth Mass Extinction, a force that won’t be satisfied until it has converted every forest, river, and organism into a dead, quantified resource.

Our culture knows this on some deep, subconscious level. The vast majority of our media revolves around a coming apocalypse—zombies, climate disasters, rogue AI.

We’re addicted to these visions of the end.

It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of the Mammonian More.

Only when every parent and worker and child is dead. When the timber wolves of Ontario and the honeybees of Anatolia have gone all but extinct. When the last vestige of life is wiped from this little blue marble–then, and only then–will Mammon have enough.

Maybe this is what Helena Valero was trying to escape. Maybe she was trying to escape the festering insecurity that leads so many to seek domination over nature, over other people, over life itself. The same insecurity that drove Cain to murder his brother.

And yet, there is no escape.

The Yanomami, like all Leaver peoples, have always been destined to face the same fate as Abel: to be murdered by Cain for the crime of living a different story.

In 2023, the Brazilian government allowed illegal miners—hungry for gold and land—to systematically invade Yanomami territory. They poisoned the rivers with mercury, decimated the game the tribe relied on, introduced new diseases, opened fire on innocent children, raped women and girls, ultimately massacring over 300 people.

This is the same old story repeated for the ten-thousandth time. The miners heeded Mammon’s demand for More, and the Yanomami paid the price.

Had God himself come down from the Heavens and asked the miners, “where are the Yanomami?” the miners would respond the way Takers always do: are we our brother’s keeper?

The opposite of the Mammonian More is not less; it is enough.

We can either learn the meaning of enough or become the authors of our own extinction.

After years of frantic flapping, our descent is undeniable. The only question left is whether we’ll meet the ground with our eyes closed, still pretending we can fly, or with them open, finally understanding the law we’ve been breaking for 12,000 years.

I’m shocked that in this discussion there isn’t mention of David Graeber and David Wengrow book, “The Dawn of Everything.”

It seems like you are using the common familiar story of the Agricultural Revolution being a fall so to speak or I think you listed it as a cliff. While I think you are right when you describe that something needs to change, in this story it seems like the only way is to go back to a time before this “fall.” At least that is what I thought before. It makes me pining for hunter gathering times.

What the Davids talk about in their book is that their wasn’t one “jump” or “leap” off into the Agricultural Revolution but that it was a seemingly gradual process, one with a whole lot more experimentation and adaptation. They show that this has political ramifications not only how we view people in the past but also for ourselves in the present. They agree with you that we are seemingly “stuck” but I feel like their exploration of how we got “stuck” is compelling and definitely something to bring into this discussion.

Love this! Right on mark